The Pillars of Raynard Kington’s Presidency

At a Grinnell College presidential search committee meeting more than a decade ago, as the committee members debated whom to select as the institution’s next president, Paul Risser ’61 (who, sadly, passed away in 2014) stood in front of a whiteboard, uncapped a marker, and suggested an exercise to rank the top 10 candidates.

The group, including Risser’s presidential search committee co-chair, Clint Korver ’89, went down the list, scrutinizing candidates’ strengths. “One of them was ambition — ambition for Grinnell and what Grinnell could possibly be,” says Korver, recalling the group’s interest in an outsider who could push the organization. “That was the sea-change moment.”

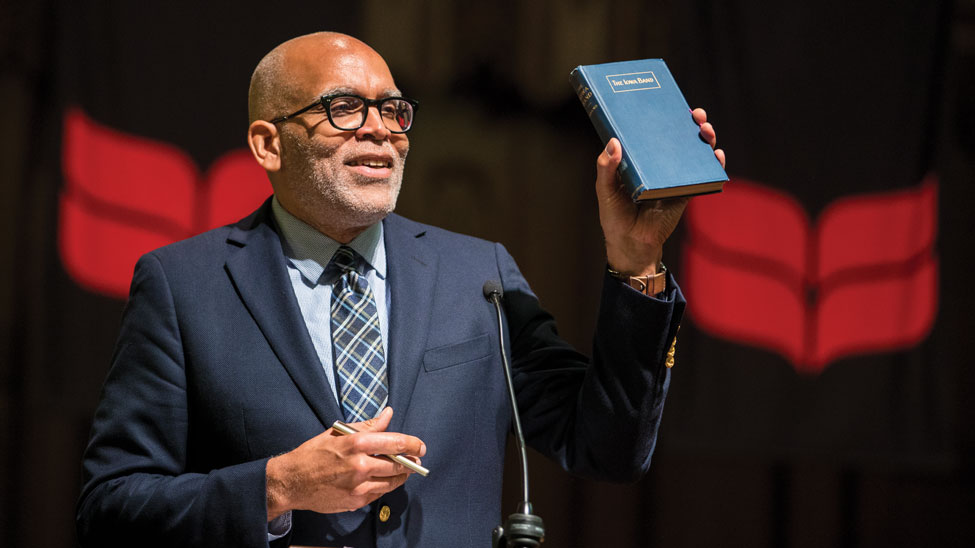

Raynard S. Kington was not the conventional choice to lead a small liberal arts college. Rather than arriving from another higher education environment, he came to Grinnell with decades of experience managing studies, people, and budgets at federal agencies — the National Institutes of Health, and, earlier, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He was methodical and data-driven. He observed things differently. He thought differently. And he pushed.

But if there were ways in which he seemed like an outlier, there were also ways that Kington could not have been a better fit. “My entire career to date has been a reflection of three core values,” Kington says. “The pursuit of academic excellence, the advancement of a diverse community, and the promotion of social responsibility. I thought Grinnell was undervalued in the community of higher education, and I thought there were opportunities to change that.”

Over the course of his 10 years with the College, those were the strengths that would help Kington make the difficult but essential decisions that would align the daily work of the institution with its most deeply held values.

“My entire career to date has been a reflection of three core values: the pursuit of academic excellence, the advancement of a diverse community, and the promotion of social responsibility.”

Meeting the financial need of students

Grinnell has long offered generous financial support to its students. Its twin policies of offering both needblind admission to domestic students, and meeting 100 percent of financial need for all students, are exceptionally rare in higher education.

Soon after arriving, Kington asked an essential but provocative question: Is the policy pair sustainable? Declining net tuition revenues and giving levels required Grinnell to rely heavily on a fluctuating endowment to meet operational costs. Could Grinnell continue to bring in such a significant share of students with financial need and afford to meet 100 percent of that need?

The question raised hackles. Abandoning the policies, said many students, faculty, and alumni, would mean abandoning part of the College’s identity. Failing to achieve a balanced funding model, countered Kington, would also mean abandoning the commitments.

Kington didn’t back away from the tension. He’s never been afraid to challenge the status quo, and he doesn’t think Grinnellians should, either. “I truly believe in the notion that colleges and universities should be marketplaces of ideas,” he says. “Especially ideas that people don’t like. They learn to deal with uncomfortable ideas, wrestle with those ideas, and have their assumptions tested.”

Joe Bagnoli, vice president for enrollment and dean of admission and financial aid, says when it became clear these policies were bedrock values, Kington offered a new way to think about achieving them. “Raynard took the position that what we’ll need to do is invest in our programs and increase demand among students and their families,” he says. “Charging a higher net price to those who can afford it will help us fund our commitments.” The plan included strengthening fundraising efforts and seeking greater market returns on endowment investments.

The ambitious effort, guided by a strategic planning process and 1,000 submitted suggestions, paid off. In 2012, Grinnell received about 2,900 applications for admission. For 2020, Grinnell received more than 8,100. Along the way, the academic profile of the student population improved — SAT scores rose almost 100 points — while the share of domestic students of color applying for admission and enrolling increased even more dramatically.

These days, with significant economic uncertainty and a challenging environment for college enrollment, such efforts have put Grinnell in an enviable position compared to its peers.

Building a cohesive global identity

When Kington arrived, the College already had a Center for International Studies and a Global Development Studies concentration. It also had regional studies, internationally focused courses, language programs, and international internships.

What it didn’t have was a way to harness all those strengths to create an institutional pillar, embedding “global” into Grinnell’s identity.

Todd Armstrong, faculty chair from 2018 to 2020 and professor of Russian, also served as the first director of the Center for International Studies from 2001 to 2008. He was appointed by Kington to co-chair a task force to address the College’s global identity.

“When I first came to the center, I was charged with creating an inventory of everything international,” he says. “And it became an impossible task, because it was almost everything.”

Kington helped guide a process that led to significantly more collaboration among the College’s divisions, academic units, off-campus study, and the Office of International Student Affairs. The result, the Institute for Global Engagement (IGE) launched in 2016. It created opportunities for faculty-led learning abroad, off-campus study, language exploration, visiting scholars, faculty collaboration, and strategic partnerships

“Raynard supported and helped facilitate a process that resulted in something new and visionary,” says Armstrong. “His leadership has helped us foreground the global as an essential and central part of what we do as an institution.”

Bringing together the humanities and social sciences

The success of IGE mirrored a similar effort to bring together the humanities and social sciences.

The divisions had a history of academic and physical separation, with departments and disciplines scattered across buildings and across campus, explains Mike Latham, former vice president for academic affairs and dean of the College. “We looked at the future of education and said, ‘The world’s moving in a much different direction. The big problems our students have to solve are inherently interdisciplinary in nature.’”

Faculty members asked what might happen if departments were intermixed, if professors collaborated in new ways, and if students and faculty pursued research in different ways.

The new Humanities and Social Studies Center (HSSC), which opened in January 2019, is the result of this philosophy of collaboration and connection. It preserves and renovates two historic campus buildings — Carnegie Hall and the Alumni Recitation Hall — and joins them with new construction to create new classrooms, inquiry labs, faculty offices, and research space for five interdisciplinary “neighborhoods.”

HSSC's four pavilions and central atrium foster synergies within through what Latham describes as “intellectual collisions.”

“Raynard saw this as an opportunity for Grinnell to do something pathbreaking, to allow our faculty to do something truly distinctive in higher education,” he says. “He framed those values in a way that was very powerful.”

Creating a more inclusive environment

In 2009, before Kington arrived, Grinnell conducted a campus climate survey, which revealed room for improvement to ensure that all members of the campus community were supported and engaged.

“The College was struggling to understand how various constituencies experienced being at Grinnell,” recalls Lakesia Johnson, assistant vice president of diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer from 2015 to 2020.

“We were struggling to figure out the concrete steps that needed to be made in order to improve their experiences,” she says.

Kington established a committee to examine in depth how various members of the Grinnell community experience being at the College and how diverse identities — geographic, ethnic, racial, religious, and socioeconomic — shape their experience.

Kington was open to immediate changes but also pushed the College to create a larger, more comprehensive plan.

“He wasn’t waiting for the perfect plan to make improvements,” says Johnson. “The combination of concrete action and planning made it possible for us to move quickly and establish momentum.”

Of the 70 recommendations presented in an early Diversity and Inclusion Plan, the College has completed or is implementing more than 60. Initiatives include training and workshops; salary and personnel reviews; and recruitment, hiring, and retention efforts.

“Raynard set the bar high, and it’s only going to get higher,” adds Johnson, who says Grinnell’s diversity and inclusion advances make it a national model in higher education.

Raising the profile for social responsibility

One of the first ideas Kington put forth in his tenure was the idea of a Grinnell College Innovator for Social Justice Prize. The award would honor change-makers around the world who creatively confronted society’s toughest challenges, including poverty, violence, natural disasters, refugee displacement, disparities in healthcare, and mass incarceration.

One of the first ideas Kington put forth in his tenure was the idea of a Grinnell College Innovator for Social Justice Prize. The award would honor change-makers around the world who creatively confronted society’s toughest challenges, including poverty, violence, natural disasters, refugee displacement, disparities in healthcare, and mass incarceration.

It would be distinctive, without question. But would the investment pay off?

Patricia Jipp Finkelman ’80 recalls being skeptical. Awarding $100,000 to two or three winners every year was an unexpected step from a president advancing a balanced funding model. She wondered if the initiative could really take hold.

Finkelman, who was on the board’s presidential search committee that brought Kington to campus (and served as Board of Trustees chair from 2015 to 2019), became a convert. “Part of raising Grinnell to the next level was raising Grinnell’s profile nationally and internationally,” she says. “The caliber of people who have won the prize, the process Grinnell goes through to make the award, and the way the College integrates prizewinners — they come to campus, students do internships with them — has transformed student experiences.”

Opeyemi Awe ’15 was one student who had such an experience because of the Grinnell Prize. While she had grown up mostly in Nebraska, she was keenly interested in West Africa. Her possibilities and purpose came into focus when Grinnell Prize winner James Kofi Annan came to campus.

Annan established Challenging Heights in 2003 to support Ghanaian children escaping slavery and child labor and to work with at-risk families. He came to Grinnell and taught a two-week course on African development.

It was exactly what Awe wanted from her Grinnell experience. “It connected my domestic, American education to the rest of the world, which is where I really wanted to be,” she says.

Awe applied for a summer internship with Challenging Heights and witnessed Annan’s holistic approach to helping children: exploring economic forces that lead parents to sell their children into slavery and offering community support to children who get out of slavery. When she returned to campus, she was able to reflect on what she’d learned.

“I found that high-touch engagement to be incredibly effective,” she says. Today, she is participating in the Schwarzman Scholar program that gives talented students the chance to develop leadership skills and build professional networks in China.

Helping Grinnellians find a meaningful “what’s next”

Although Grinnell’s individually advised curriculum has long set it apart from other schools, its career services have not always risen to the same standard. The College had established itself as a top producer of graduates who go on to earn doctorates. It was not as successful at launching graduates straight into the job market.

CLS Leadership Donors

- Patricia Jipp Finkelman ’80 and Daniel Finkelman ’77

- Pamela Crist Fuson ’68 and Harold “Hal” Fuson ’67

- Michael Kahn ’74 and Virginia Munger Kahn ’76

- Dr. J. Michael Powers ’67 and Linda Bird Powers ’67

- Penny Bender Sebring ’64 and Charles Ashby Lewis

Kington saw that the moment had come to develop services that would help students thrive not just at Grinnell, but in all the things Grinnellians might do after graduation.

“Employment opportunities were being missed from both sides,” says Finkelman. “Students weren’t being exposed to job opportunities, and employers were not aware of Grinnell.”

That belief that Grinnell had a responsibility to support students in all their future endeavors led to the creation of Center for Careers, Life, and Service (CLS), which could not have been launched without significant philanthropic investment from alumni and friends (see leadership donor recognition list above).

A combination of experiential learning and facilitated exploration is now part of every incoming student’s Grinnell experience as soon as they arrive on campus. The experiences and resources are designed to help students connect their personal, civic, and professional identities to purpose, pathway, and meaning.

It’s worked: According to a Gallup-Purdue report, most college students visit their career services office only once or twice prior to graduation, often waiting until their senior year. During the 2018–19 academic year, more than 84 percent of Grinnell’s student body connected with CLS an average of 5.6 times. Nearly 5,100 employers targeted more than 20,000 internship and full-time job opportunities to Grinnell students.

“Grinnell is now being viewed as a leader in this space because of innovative things CLS is doing,” Finkelman says.

Even at a time of extreme uncertainty for new graduates, the work students have put in with the support of the CLS gives them an advantage. “These are extraordinary times to be a student and to graduate from college,” says Kington, “but I think Grinnellians are up to the task.”

Leading in a crisis

If many of the big changes that Kington helped implement were the result of careful, long-term processes and decision-making, Kington’s final major acts as president were the swift, decisive moves he made in the face of a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic.

In the early months of 2020, COVID-19’s grip was just starting to take hold in the United States. Kington drew on his extensive scientific background, along with the data gathered by a small team of administrative leaders, to make the decision to close down campus and move to online learning. Grinnell was among the very first colleges to commit to this extraordinary step (see “They Moved Mountains,” Summer issue, page 20). In the coming weeks, nearly every college in the nation would follow suit.

As Kington departed Grinnell for a new chapter as head of school at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, he left Grinnell at a time that felt especially tenuous in the world. But the foundational work of his presidency leaves the College in a strong position.

When Risser uncapped his marker a decade ago to ask the presidential search committee members if they were ready for an ambitious president like Kington, they knew that they would be choosing someone who was unconventional.

But then again, so are Grinnellians. During his presidency, Kington pushed Grinnell to make the hard decisions and big commitments that brought the College greater recognition among its peers, better outcomes for its students, and closer alignment with its highest aspirations.

Kington wasn’t like the others. But his 10 years at the College have proven that he was exactly right for Grinnell.

Raynard Kington: A Presidential Timeline

- 2010

- Grinnell College’s Board of Trustees announces Raynard S. Kington, M.D., M.B.A., Ph.D., as Grinnell College’s 13th president on Aug. 1, 2010.

- 2011

- The College awards the first Grinnell College Innovator for Social Justice Prize.

- 2013

- The Board of Trustees votes to retain the policies of need-blind admission and meeting 100 percent of demonstrated financial need for domestic students.

- The Innovation Fund is established, providing grants of up to $500,000 to enrich campus life.

- The Center for Careers, Life, and Service (CLS) is launched.

- 2016

- The Institute for Global Engagement is established.

- 2018

- New First-Year Experience course focuses on helping new students develop skills that will contribute to their academic engagement and personal well-being.

- 2019

- The newly constructed portion of the Humanities and Social Studies Center opens.

- The African American Museum of Iowa recognizes President Kington as a History Maker.

- The Campaign for Grinnell College, an ambitious $175 million campaign and Grinnell’s first comprehensive campaign in nearly 20 years, is publicly launched.

- 2020

- On March 10, a day before the COVID-19 outbreak was declared a global pandemic, President Kington announces the decision to close campus and move to distance learning. Grinnell is the first Iowa college to do so.