A Light Switch Went On

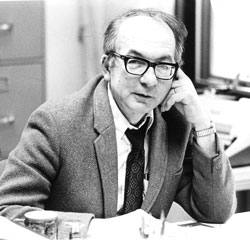

Whether it was by luck or design, Sarah Purcell ’92 found a mentor in the first faculty member she met at Grinnell — Al Jones ’50, L.F. Parker Professor of History. In a department full of excellent professors, Jones was a legend.

In the fall of 1988, Purcell enrolled in his First-Year Tutorial on Culture and Power. That year, as interim director of the Rosenfield Program in Public Affairs, International Relations, and Human Rights, Jones was instrumental in organizing a convocation series and film series on the topic of culture and power. Purcell attended the lectures, watched films, and read novels, all through an historical lens. She even had lunch with one of the convocation speakers, Edward Said, a spokesman for the Palestinian people.

In the fall of 1988, Purcell enrolled in his First-Year Tutorial on Culture and Power. That year, as interim director of the Rosenfield Program in Public Affairs, International Relations, and Human Rights, Jones was instrumental in organizing a convocation series and film series on the topic of culture and power. Purcell attended the lectures, watched films, and read novels, all through an historical lens. She even had lunch with one of the convocation speakers, Edward Said, a spokesman for the Palestinian people.

“It was a hugely formative experience for me,” she says. Purcell declared a major in history her first year and asked Jones to be her adviser.

At one point that year, he asked her, “Have you ever thought about being a professor?”

“A light switch went on,” Purcell says. Before that she hadn’t connected history to a particular career path. She just knew she loved it.

Flash forward 30-some years to a second-floor classroom in the Bucksbaum Center for the Arts. Purcell waits eagerly for her students in History of Popular Culture. They enter the room in pairs to have short peer review conferences about their research proposals.

Purcell invites each student reviewer to speak first before sharing her views. They focus first on the strengths of the student’s proposal. Then they discuss improvements the student could make, like shortening a paragraph-long thesis statement to a single sentence or correcting flawed footnotes.

“What the hell?” she says in a lighthearted way. “You’re history majors. You know how important footnotes are.” Then she smiles at them, pushes up her glasses, and says, “I yell at you with love, only with love.” But they know she’s serious about the footnotes.

Whether she’s working with students in her classes or one-on-one with research assistants, providing close attention and care is second nature to Purcell.

Talent Spotter

Purcell, who now holds the same named chair as her first mentor in history, is an enthusiastic, dynamic, encouraging mentor of her own students. In 2019, she received the Council on Undergraduate Research’s inaugural award for excellence in mentoring in the social sciences.

Purcell, who now holds the same named chair as her first mentor in history, is an enthusiastic, dynamic, encouraging mentor of her own students. In 2019, she received the Council on Undergraduate Research’s inaugural award for excellence in mentoring in the social sciences.

In his letter supporting Purcell’s nomination for the award, Michael Latham, then dean of the College, wrote, “While Grinnell has a strong culture of faculty mentorship of student research experiences, one thing that really makes Professor Purcell stand out as a research mentor is her ability to work with students as research collaborators — despite the fact that she works in a field in which collaboration is not the norm.”

One of the qualities Purcell looks for in student collaborators is enjoyment of the research process. She spotted that in Sam Nakahira ’19 when Nakahira took History 100 with Purcell as a first-year student.

“She got really deeply into sources,” Purcell says, “engaging with them on a level really beyond what was required … especially at the introductory level. She also gave an extremely good presentation based on her research, so I thought she had teaching potential too.”

Purcell asked Nakahira if she’d ever thought about being a professor. Nakahira hadn’t, and the idea intrigued her. She became a Mellon Mays Fellow as well as one of Purcell’s research collaborators and advisee.

Nakahira worked with Purcell on a summer Mentored Advanced Project (MAP) on digital history and slavery. They visited Louisiana State University’s Special Collections

to do primary research. Nakahira sought information about the interior spaces of a Louisiana

sugar plantation, so she pored over receipts for furniture, correspondence, and financial and tax records. She also learned about daily life through grocery lists and

schedules for slave workers and the tasks they were assigned.

“She really helped me feel comfortable with different research methods,” Nakahira says. For her Mellon Mays research project on Japanese American agriculture after World War II, she and Purcell discussed oral history, a technique Purcell last used herself when working

as Al Jones’ student research assistant in 1990.

“She gave me the confidence to do things,” Nakahira says. “Her support was empowering.”

Advice Not Taken

Purcell encourages all her students to take a year off before pursuing graduate school, though she didn’t follow that advice herself. “What was I going to do? Work in a bank for a year?” she jokes. “I knew grad school was the right step for me.” Winning a Beinecke Scholarship that paid for the first two years of her program was reasonable confirmation of that assessment. So off to Brown University she went for her doctorate in history.

Next she taught at Central Michigan University for three years. While she enjoyed her work there, she really wanted to teach at a liberal arts college. Then an opening in the history department at Grinnell caught her eye. She’s been teaching here since 2000.

Mentors Make a Difference

Most Grinnell grads are not destined to become professors. Other careers beckon, and Purcell is fully aware of that. The skills she teaches transfer to many other professions.

Hayes Gardner ’15 especially values her effect on his writing. Purcell gave him specific tips that helped him not only relay information correctly, but to write concisely and clearly as well.

“My writing vastly improved throughout my time at Grinnell,” he says. “I’m currently a journalist, so that’s extra important to me. She definitely morphed me into a better

writer.”

Purcell recommended Gardner for a summer internship with the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, which gave him great reporting experience. When he graduated, Gardner was pretty sure he wanted to go into sports journalism, but first he wanted to do a year with a service organization. Purcell encouraged him to do freelance writing on the side.

He thought it would be difficult to find the work, but after sending a few emails, he landed a gig covering high school sports for The Oregonian, the largest paper in Oregon. Without her

encouragement, Gardner isn’t sure he would have tried freelancing.

“I didn’t think it would be possible,” he says, but he wound up freelancing for years. “That was the foundation for my current career,” he says. Gardner is now a sports writer for the Courier-Journal, Louisville, Kentucky.

Even years later, Purcell shares job opportunities and connections. “It’s great to still have a mentor like that even after you graduate,” Gardner says.

Getting to know each other during a summer MAP project helped forge that lasting connection.

“It’s nice to have the luxury to know each other as people,” Purcell says.

While Grinnell faculty and students have enjoyed close mentoring for decades, one benefit

of formal programs such as Mellon Mays and MAPs is that mentoring becomes even more accessible to students. And as Sarah Purcell can attest, who knows where that may lead?