One of the Most Influential Grinnellians

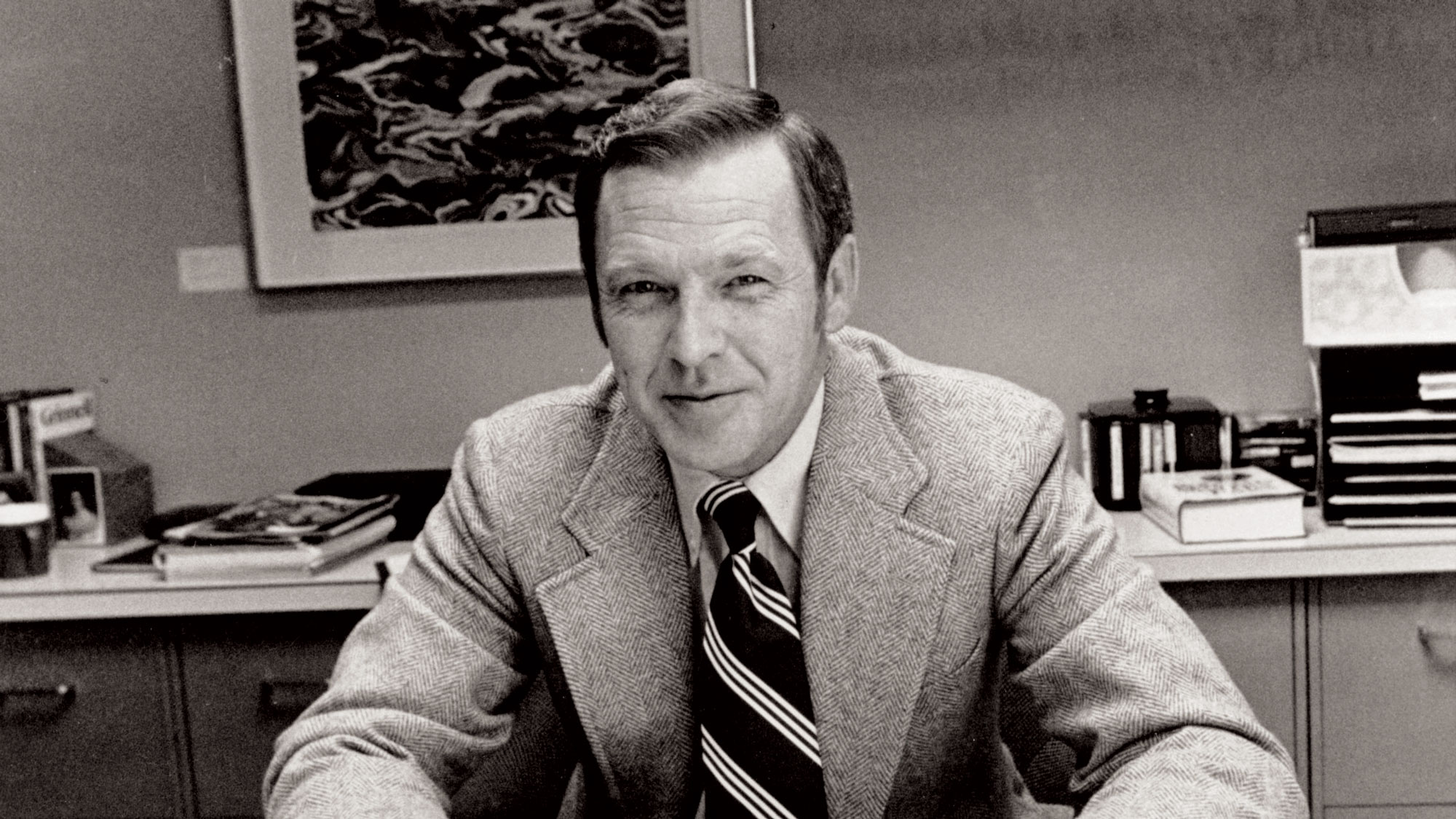

Grinnell College may well have been a different place without the long, dedicated service of Waldo “Wally” Walker.

The bulk of his career was spent in the administration, and he thoroughly enjoyed the work. He had several different titles over the years and at least once was in the running for the top job — president. He served several presidents, from Howard Bowen to Pamela Ferguson, loyally and thoughtfully.

Some of the work Walker did was thankless — like telling faculty and staff that their positions were eliminated due to budget cuts. Through it all, he supported the continuous improvement of Grinnell’s academic quality, because he valued the College as an institution and its role in Iowa and the country.

An Iowa boy who appreciated differences

Walker, who died in Grinnell on Aug. 28, 2020, at the age of 89, grew up in Fayette, a small farming town in northeast Iowa. He was close friends with Vera Stepp, a Black girl whose family ran a well-known produce farm. For a young white man from rural Iowa in the 1940s, that was surely unusual.

It was in the Army, however, where Walker had extended, significant interactions with people of color, especially Black people.

He enlisted in 1953 after completing his bachelor’s degree at Upper Iowa University in Fayette. It was near the end of the Korean War, and his decision to enlist, rather than waiting to be drafted and possibly sent to Korea, paid off. He spent his two years at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, where he helped soldiers move to their next assignments.

Walker’s time in the Army was crucial to the development of his racial awareness and understanding of racial inequities, which became important to his work at Grinnell.

“Wally learned a lot about equality” by serving with Black soldiers, says Frank Thomas ’71, who was good friends with Walker. Walker talked with him about his time in the Army. “Wally had a great deal of respect for a master sergeant, who was Black,” Thomas says.

In his work with the master sergeant, Walker observed how Black soldiers, who were following all the rules and obeying orders, were nevertheless denied access in ways that were injurious to them. That awareness stayed with Walker throughout his life and work.

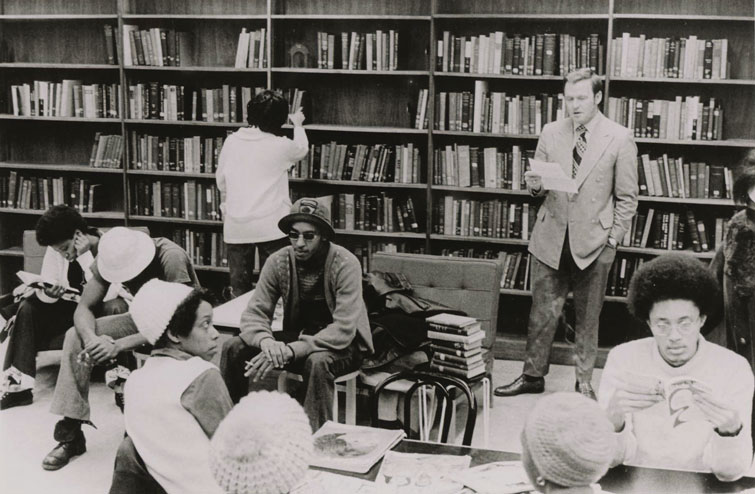

In November 1971, a few dozen members of Concerned Black Students occupied Burling Library and issued a manifesto demanding several changes to improve campus life for Black students and faculty. Walker was the lead negotiator on the College’s behalf.

A photo of him during negotiations shows what appears to be a casual pose, but Walker was actually trying to hide his nerves. Years later he told Thomas, “I was so nervous, confronting the students at that time, that I was visibly shaking.”

Walker became friends with a number of the students who occupied the library, including Barry Huff ’73 (deceased, see Family Creates Internship Fund in Memory of Trustee G. Barry Huff ’73), whom Walker frequently referred to as his “son.”

Trustee Shelley Floyd ’72, who was president of the Student Government Association that year and worked closely with Walker, says he was tough and wouldn’t abide law-breaking but he empathized with the Black students. He listened to their concerns.

From faculty member to dean, finding his best fit

In 1955, after his tour with the Army, Walker headed to grad school at the University of Iowa on the GI bill. He started teaching biology at Grinnell in 1958. His empathy for and understanding of students were qualities that stood out.

James Stauss, dean of the College, was on the lookout for faculty who understood students’ perspectives during the turbulent 1960s — an era of protests over civil rights, women’s rights, and the Vietnam War. He tapped Walker to become an associate dean, a new position.

Another reason for the new position was that President Bowen had won a grant from the Hill Family Foundation to support a “junior liberal arts experience.”

Another reason for the new position was that President Bowen had won a grant from the Hill Family Foundation to support a “junior liberal arts experience.”

Running that new program “was dumped in my lap,” Walker said.

He invited three other faculty members to join him in developing a reading list and exam. They met all summer, up to three hours per day, and “selected great books that we would assign to the students,” he said — books like Moby Dick, On the Origin of Species, and Madame Bovary. “That’s my major liberal arts training right there. I learned so much about the world then.”

The program lasted only three years, but “it was one of the most interesting educational experiments I was involved with,” Walker said.

The experience also may have given him a sense of how he could positively influence Grinnell on a broader scale.

“Wally could see the College’s potential, and he bought into it,” says George Drake ’56, president emeritus, whom Walker served as executive vice president. “He was loyal to Grinnell College and its ideal.”

In service to all, for the greater good of Grinnell

The early 1970s brought tremendous changes to Grinnell’s academic experience. The faculty voted to abolish general education requirements and adopt the “no requirements” curriculum in the fall of 1970. One of those requirements had been a one-year humanities course that included significant writing instruction from expert faculty.

In its place, a new, one-semester course was created — the course now known as the First-Year Tutorial. It was taught by faculty across all disciplines, including professors who didn’t feel well prepared to teach writing.

Walker could clearly see the difficulties arising for professors and students. “[T]he reality is that many of the tutorial instructors have neither the expertise to teach composition skills, nor have they had the pedagogical experience in teaching these skills to aid students in correcting their writing problems,” he wrote in a 1973 memo.

He talked with Peter Connelly and Don Irving, professors of English, and developed a two-part proposal: 1) Faculty members would offer a selection of writing-intensive introductory courses requiring at least five papers, so that “students will be writing about something of substance in which they have more interest than they would in composition drills”; and 2) faculty who taught these courses or tutorials would be offered a one-week summer seminar on how to teach writing.

Despite the tight budgets of the time, Walker also offered to pay faculty for their time taking the seminar. He wanted to encourage them to participate in it, not mandate it.

Walker was a proactive dean, says Drake. He didn’t wait around for ideas.

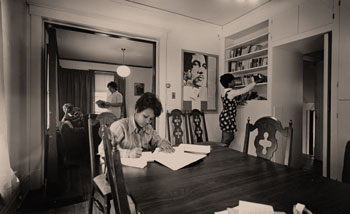

About the same time, Walker was also quietly creating support for students and their writing. In the early days of the tutorial, “students were wandering around in despair,” about their writing said Mathilda Liberman, lecturer emerita in English.

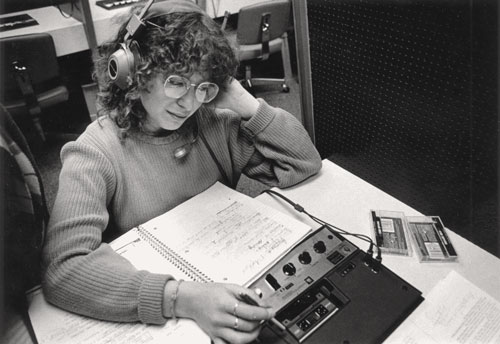

Walker asked Liberman to meet with a few of the students one by one to discuss their writing problems, and soon the Writing Lab was born. Initially, Liberman was director with the assistance of a couple of resident advisers, but the work was crucial and the need was ongoing. Since Walker had a good command of the budget, he figured out a way to pay for it.

“Trying to squeeze in two or three extra positions at the College just to help students with writing was a big step,” Drake says.

Walker believed deeply in the Writing Lab, the Math Lab, and other support services for students. “Those things developed at a critical time,” Drake says.

Lasting impact

Grinnell’s academic rigor and reputation experienced major leaps during the Wally Walker years. Don Smith, professor emeritus of history, believes Walker is second only to Joe Rosenfield ’25 in terms of his importance to the College during the last 50 years. Walker’s longevity and institutional knowledge made him invaluable. His warm humor, ready smile, and ability to tell a good story made him well-liked.

During his 43-year career at Grinnell, his influence was expressed and felt in myriad ways — in his care for students, in his care for faculty and staff, and in his devotion to the College overall.

Share your stories about Wally Walker.

Walker with students George Herman ’69 and Susan Sleeper ’69 using an electron microscope