Touchable: The Value of Hands-on Research with the Grinnell College Art Collection

In the basement of Burling Library, in the perfectly chilled Print and Drawing Study Room, on an even chillier February afternoon in Grinnell, students eagerly crowded around Jiayun Chen ’19 and Susan Wood, professor of art history at Oakland University. Their attention remained fixed upon a small marble head, resting on a soft white pillow. Chen had examined the portrait before, but this time, she found something new.

Art objects offer opportunities for new discoveries

This particular head is one of three possibly ancient sculpted heads, which form a part of the College’s art collection and are some of the artifacts that students can research. Monessa Cummins, associate professor of classics, heard about the heads from Jerry Lalonde, professor emeritus of classics. “Jerry just kept saying someone needs to work on those sculpted heads,” Cummins says.

For years, very little was known of the stone portraits. When Andrew Stewart, a professor from the University of California Berkeley who specializes in Greek sculpture, visited campus in 2015 for a lecture, he examined the heads. Stewart identified one as Roman and authentic and the other two as possibly Greek and worthy of study.

A seed was planted, and a few years later when Chen approached Cummins one spring about doing a Mentored Advanced Project (MAP), Cummins suggested that she work on one of the ancient heads. They looked at the three heads and settled upon the Roman head for Chen’s research, thinking it might be more distinctive.

Chen, who had studied Greek sculpture at Grinnell, used the following summer at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens (thanks to the Gerald Lalonde Fellowship) and her semester abroad in Rome to visit as many museums as possible to gather images of portrait heads that resembled the Grinnell portrait. Based on her portfolio of comparable heads, Chen confirmed Stewart’s conjecture that the portrait could be dated to the third century, and she narrowed the range to about 225–300 C.E.

That’s when it got interesting. Third-century Roman portraiture is a mess, Chen says, “because there are lots of coexisting styles, and then you have this lack of material culture. You have fewer monuments, which could show you the change in imperial portraiture.”

Cummins invited Susan Wood, who wrote a book on third-century Roman portraiture, to give a lecture on the subject and inspect the sculpture in person with Chen. The third century in Rome was a time of economic stress, as the empire was coming apart at the seams. Portraiture of the time, not immune from these pressures, shifted to a very hard abstract style, according to Wood. “It isn’t some kind of spiritual angst. It’s time, pressure, and money.” Wood says these factors resulted in the recycling of old portraits, which sculptors would refashion into portraits of other people.

The practice of re-cutting portraits was common in Rome. Whenever an emperor came to a bad end, like Nero or Domitian, he got the damnatio memoriae treatment, or “condemnation of memory.” How did that work in practical terms? They would chisel the emperor’s name out of inscriptions and destroy his portrait. Sometimes the sculptures were vandalized, but other times, the Romans recycled the artwork. After all, why wreck a perfectly good piece of marble?

Sometimes, the handiwork would be obvious, like a badly Photoshopped image or a botched plastic surgery, but other times, the adapters would skillfully re-cut the portraits, making it difficult to discern whether it was re-cut at all.

But what about the Roman head in the College’s art collection? Had it been re-cut? That’s what Chen wanted to know, and that’s why a throng of students gathered around her in the basement of Burling as she ran her fingers across the marble.

Fresh eyes on the object itself

Before Wood’s visit, Chen sent her photographs of the portrait. Wood did not see any signs of re-cutting. But when Chen and Wood took a closer look at the portrait with fresh eyes, new details appeared. Chen found some overlapping traces of stippled hair, short locks of hair chiseled with what appeared to be simple strokes, which Wood believes to be the original traces of the hair and the sculptor’s attempt to re-cut the sculpture and create a new hairstyle and thus, a new portrait.

They found more. Chen asked, “What about the ears?” They both agreed the ears looked suspicious, almost unfinished. Wood explained the apparently unfinished ear holes, “the hairstyle change would have necessitated cutting back around the ears,” and surmised that the sculptor might have tried to drill the volute of the ear and then given up.

Chen also noticed something peculiar about the nostrils of the portrait. There were none. “Don’t Roman portrait sculptures usually have little drilled holes for the nostrils?” she asked Wood. It didn’t look like the result of damage, because it was too even. It appeared to Chen and Wood that somebody had cut down a larger nose to change the features of the face.

The face, seemingly of a young boy, was also notable. It didn’t look like any members of imperial families that Wood knew, so she and Chen believe it to be a funerary portrait. The main reason for making portraits of children was because they had died young and their parents wanted memorials of them in the family tomb.

Although there is still much to be known about the head, Chen’s research uncovered new details. Doing so required a hands-on approach, though.

Hands-on leads to new ideas

Chen could have visited all the museums in the world and looked at digital images of the sculpture for days on end, but nothing compares to the opportunity for hands-on research. As much as Chen enjoys examining ancient sculptures in museums, she relishes the opportunity to feel the objects with her own hands. “Even though you have gloves on, you can actually feel the sculpture, feel how polished it is.”

Wood also believes in the necessity of this hands-on approach. “I’m always telling my students, photographs are not good enough. You’ve got to see the real thing. Even very good photographs never tell you the whole story.”

Cummins, as well, could talk for days about the value of working with these material objects. “For engaging the imagination, for close attention to detail, and the kind of repeated, continual observation that eventually yields a thought, you can’t beat it.” When confronted with a physical object, she finds students are more motivated to observe it carefully.

Grinnell students have the unique opportunity to handle the items in the College’s collection with their own hands. Although the authenticity of the objects is not necessarily in question, the lack of a provenance — specific knowledge about the objects’ origins — offers students the challenge of trying to place the objects in their chronological and cultural framework on the basis of their own close observations and study of similar objects.

Value of original undergraduate research

Conducting original research as an undergraduate is a great challenge, and Cummins is ebullient in her praise of Chen’s dedication to this research. “There’s no body of knowledge out there to help you reach that thesis in a certain sense. You are on your own and students in this situation are really forced on their own resources to figure things out, and to discover how really hard that is, to have an original thought about something. They really learn experientially what it is to research. And it’s a whole new ball game.”

In the narrow field of third-century Roman portraiture, Chen has developed a level of expertise seldom found in undergraduate study. During her research, and since, Chen plays a game with herself in museums. “I go to a portrait; I don’t look at the information below. And then I try to date it and then compare my answer to the labels.” Sometimes, she’s wrong. But other times, she thinks, “Is the museum wrong or am I wrong?”

Chen’s knowledge is valuable beyond showing off at museums, though.

“It’s powerful to know that you actually know something. Because I had been talking to people about a portrait so much, I feel like I have really mastered the material. And that’s a great feeling.”

Chen’s research on the Roman head represents the culmination of her studies at Grinnell. Through her classics coursework, MAP, and summer coursework at other institutions, she built up a wealth of experience. The research paper Chen wrote about the Roman head for her MAP earned one of three Phi Beta Kappa awards given to Grinnell students. Chen gained valuable experience through presenting her work at a conference and talking with other scholars in the field about it. She presented her findings in Lincoln, Nebraska, at a meeting of the Classical Association of the Middle West and South, a regional organization of classicists. In part because of these experiences, Chen was accepted into a Ph.D. program in classical studies at Columbia University in New York City.

An unlikely connection — classics and chemistry

Other objects in the College’s art collection are used for research too, and not just in the art or classics departments. Chemists are getting in on the fun as well.

Nora Madrigal ’19 and Ben Hoekstra ’19 were looking for something to research in their Chemistry 358: Instrumental Analysis class. Madrigal, a classics and chemistry double major, and Hoekstra, a chemistry major, had both taken a classics course with Cummins and were interested in doing research with an ancient object from the College’s collection. At the suggestion of Angelo Mercado, associate professor of classics, they met with Lesley Wright, director of the Grinnell College Museum of Art (see Page 6), and decided upon the Reed Painter vase as the object of their study.

In 1975, Grinnell College acquired a lekythos, an ancient Greek vessel generally used to store scented oil, which was common in Athens from 475 BCE to 400 BCE. The lekythos had been in the possession of former Grinnell President John H. T. Main before being donated to the collection. Its provenance prior to the beginning of the 20th century is unknown. As part of a 2005 MAP, Nathaniel Jones ’06 performed an iconographic analysis of the exterior of the lekythos, which he determined to be the work of the Reed Painter. But questions remained about the vase’s use in antiquity, questions which could not be answered through visual observation alone.

Based on Jones’ previous research, Madrigal and Hoekstra suspected that the vase had been used as a funerary container for scented oils, but they wanted to confirm that hunch. So, with the assistance of Leslie Lyons, professor of chemistry, they conducted various chemical experiments to determine the composition of the vase and identify any organic compounds present in the interior of the vessel. They used another lekythos from the collection as a control to which they could compare their results.

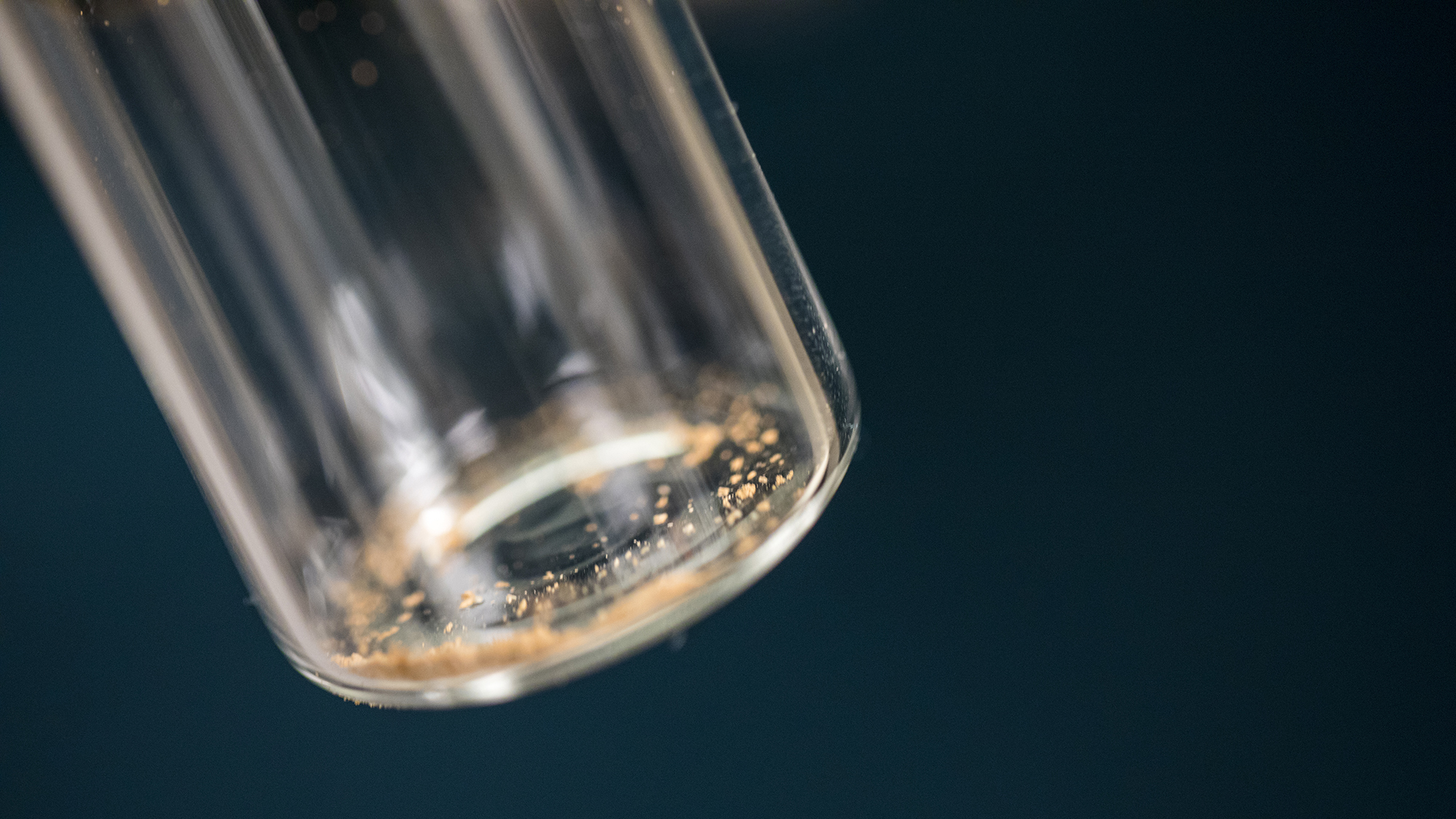

Madrigal and Hoekstra performed organic residue analysis on the lekythoi by extracting organic compounds from the porous interior of the vases. Madrigal and Hoekstra hypothesized that they would be able to identify compounds commonly found in olive oil, which would confirm its use as a funerary vessel in antiquity. Once the extracted materials were prepared, they used tandem gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to separate and identify any extracted compounds, a process that works particularly well for analyzing trace amounts of organic residues. Additionally, the pair conducted X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis on the surfaces of both lekythoi to determine the elemental composition of both the clay and the black glaze present on each.

Based on the results of the GC-MS analysis, Madrigal and Hoekstra could not identify any compounds associated with olive oil in the Reed Painter vase. They were, however, able to identify one compound, phthalic acid isobutyl octyl ester, in both of the vases, which suggests a possible link to the storage of scented oils. Previous research in the field has often explained the presence of this compound as evidence of environmental contamination, but it has also been found to be a component of the essential oils of various plants, especially those with a strong odor. In particular, this ester has been identified in rose oil as well as in members of the Acanthaceae family, found extensively around the Mediterranean. These connections, tenuous as they are, provide a potentially promising connection to the funerary use of the Reed Painter vase in antiquity. With more time, Madrigal says, they could ask other questions, and possibly glean other answers.

Asking the right questions

As any researcher can attest, questions often lead to more questions. But it’s important to ask the right questions. And sometimes asking the question is the most important part.

Wright is a big advocate of these research projects. “Who knows what we might learn? Research is always instructive, whether or not we find out it’s by somebody we can name or it has some great significance. It’s the process of learning how to do that research that is so valuable for students. They use art as a primary resource that opens up other questions, which was certainly the case for Nora and Ben.”

Even though they were unable to confirm the questions about the functional nature of the vase, the research experience proved valuable for the students involved. Madrigal reflects on the experience: “This was basically the best chance I got to directly combine the two subjects that I had been studying for four years.” She sees a lot of potential for similar interdisciplinary research to be done with items from the College’s collection. Chemists might not think of the art collection as a resource for potential research projects, but Madrigal thinks more students should consider the option. “I think there’s definitely a lot of information to be gained by analyzing artifacts — not just classical artifacts, but any artifacts — through a scientific lens. Adding that scientific analysis can really enhance our understanding of the pieces themselves, their history, and their use.”

Students and faculty from across the curriculum make use of the College’s art collection, but the hope is that it will continue to be used even more for research like this, which benefits both students and the College. For students, the objects prove great fodder for original research, enhancing their academic experience and preparedness for graduate school environments. And for the College, this type of interdisciplinary, deep research yields new discoveries about some of the very old objects in the art collection.