The 60-Second Syllabus

What makes a college course relevant? Compelling? Career-changing? Our world-class faculty members’ expertise and creativity is infused into dozens of unique course offerings each semester. So, what have students been learning lately and why does it matter? Check out our sampling of 60-second syllabi, where professors reveal what makes their courses tick.

When Erick Leggans ’05 took chemistry courses as a Grinnell student, structures to help him succeed were embedded right into the syllabus. For example, he was required to join a group of classmates to collaborate on problem sets. The sequence of lessons in the course was carefully scaffolded to build skills in ways that would prepare him for professor-guided lab research later.

The approach worked: Leggans is now a tenured chemistry professor at Grinnell, and he uses his own courses, including Organic Chemistry, to offer today’s students the kinds of tools and opportunities that helped him succeed. “I want to give students the materials, structures, and guidance they need to pass this course, and also to go from here and to contribute to any field,” he says.

Across all divisions, Grinnell faculty are committed to teaching courses that do more than just impart knowledge. They also build skills that are useful beyond the classroom.

To learn more, we asked six professors to take us inside one of their courses and share their insider insights.

PHI 121

PHI 121

Philosophy for Life

Taught by Assistant Professor of Philosophy Jennifer Dobe

Description

Students grapple with timeless, practical questions: How should I live? What is happiness? What kind of life should I pursue? Using philosophical texts and robust classroom discussion, students explore a variety of ways to interpret the world. “We want students to feel empowered as philosophers in their own lives and to see the discipline as indispensable,” says Dobe.

Selected materials

- “Letter to Menoeceus,” Epicurus

- The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching, Thich Nhat Hanh

- Your Silence Will Not Protect You, Audre Lorde

Essential question

Students consider Robert Nozick’s “Experience Machine” thought experiment, which was first proposed in the 1970s: If you could enter into and program a machine to give you any experiences you wished, feel these experiences as though they are your lived reality, and have them continuously for the rest of your life, would you choose to enter into this machine for the rest of your life?

“It’s a way of looking at the way we feel and think about the unknown and connecting with a reality that is other than us,” says Dobe.

Beyond the course

Dobe hopes that the course helps students internalize the idea that life is not something that happens “outside of them,” but that they must seek to be active participants in it right now. “One student told me that at the beginning of the course, he wasn’t sure what philosophy had to do with life at all, but by the end, he believed that philosophy was integral to everything having to do with life,” she says. “I hope that the course helps students feel more at home and empowered in the lives they are creating.”

ANT 295

ANT 295

Graphic Medicine: Reading Medical Comics Anthropologically

Taught by Professor of Anthropology Maria Tapias with Support from Tilly Woodward, Curator of Academic and Community Outreach, Grinnell College Museum of Art

Selected materials

- Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud

- Aliceheimer’s: Alzheimer’s through the Looking Glass, Dana Walrath

- Coma, Zara Slattery

Description

Medical graphic novels use a combination of words and images to illuminate the culture of medicine, health inequities, and cultural understandings of illness.

Students read books on comics theory as well as graphic medical comics and graphic novels to learn how they work. These serve as a starting point for students to create their own graphic medicine project.

The course helps students synthesize medical anthropology, ethnographic field methods, comic theory, and art — a combination of diverse fields that Tapias says makes it “a quintessential liberal arts course.”

Key project

Students conduct in-depth interviews with someone close to them, such as a family member or close friend, who has experienced a health-related issue of some kind, from cancer treatment to menopause. They use the interview as a jumping-off point for a visual project, such as a poster or comic book, for public display in the Bucksbaum Rotunda.

Tapias says that students find the conversations valuable for more than just their class projects. “I told them: You’re going to learn something about your parents, brother, or sister that you don’t know. That’s an opportunity,” she says. “Their history is your history.”

Beyond the course

While the course itself is uniquely specific in its aims, Tapias wants students to walk away with broadly applicable insights. “My hope for the students is that they appreciate the power of storytelling as a vehicle for increased empathy,” she says. “I also secretly hope that students recognize the importance of having a creative outlet in their post-Grinnell lives. I began this class with the strong conviction that anyone can make a beautiful comic. Students proved me right.”

ARH 103

ARH 103

Introduction to Art History

Taught by Assistant Professor of Art History Eiran Shea

Unlike a traditional introduction to art history that offers a broad but surface-level overview of world art, this reimagined introductory course aims to build students’ analytic skills by focusing on 13 specific works of art and architecture, including those in the College’s art collection and the town of Grinnell itself.

Students learn visual analysis by looking closely at and describing art objects, considering how various elements contribute to meaning, and aligning their evaluations with historical material and analysis.

Selected materials

Students study numerous objects that are physically located in Grinnell and pair them with a variety of essays and other materials. These objects include:

- a Buddha sculpture in the HSSC

- a high-quality facsimile of Early Spring by Northern Song dynasty painter Guo Xi

- The “jewel box” bank in Grinnell

Object lessons

Shea, an East Asian specialist, spends a week helping students understand Guo Xi’s Early Spring, a scroll painting that features trees, sloping landscapes, and heavy mists. “In one class, we talk about what makes Chinese landscape painting special. In another, we spend time in the Print and Drawing Study Room looking at this very high-quality facsimile. In a third, we look at related work and read primary source documents written by the artist,” she says. “It’s an approach that allows you to engage much more deeply with certain topics.”

Beyond the course

Shea hopes students gain skills to look at any art object and find meaning. “They can understand what the material it’s made of is telling them, what certain patterns might be communicating, and how it might have been understood as a social object,” she says. “I want them to be able to walk into any museum, anywhere in the world, and feel like they can engage with its contents visually. Visual literacy is important, whether you go into computer science, biology, or sociology.”

“We considered the Merchants’ National Bank by Louis Sullivan for one of our essays,” says Natalia Ramirez Jimenez ’24. “The close analysis of art pieces that were accessible to us was great to further my interest in art.”

CHM 221

CHM 221

Organic Chemistry

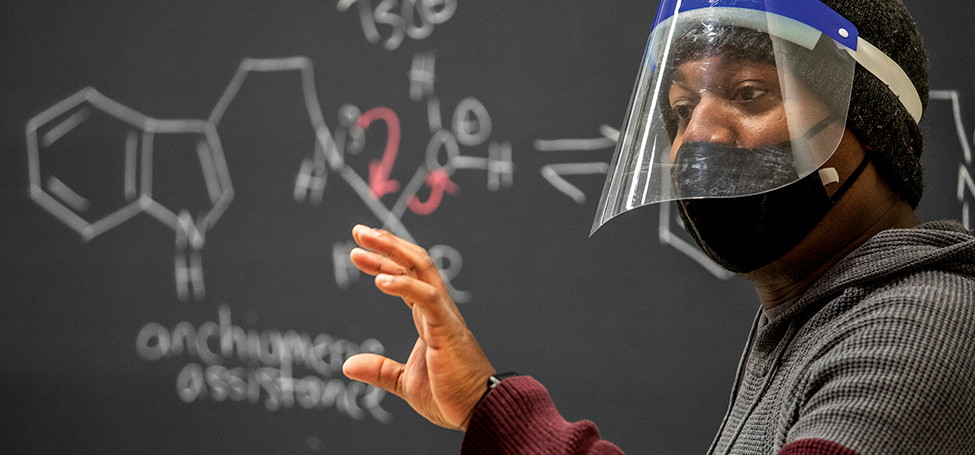

Taught by Professor of Chemistry Erick Leggans ’05

What it’s about

The 200-level course, which has a lab component, is described as “a comprehensive study of organic structures, syntheses, reactions, and spectroscopy of organic compounds,” but Leggans says there’s a simpler description: “It’s the study of life.”

Selected materials

- Organic Chemistry

- Laboratory notebook

- Molecular model

Key project

One highlight is a lab in which students create a banana-scented ester compound known as isoamyl acetate. (It starts as two different solutions that have decidedly less pleasant smells.)

While the project itself is an enjoyable one, Leggans notes that it’s the culmination of a series of smaller skills that students have learned in previous weeks: filtration, extraction, and evaporation, for example.

“What will I take away from this course? No matter what, just keep trying. Whether it was a failed attempt in the synthesis lab or struggling with a mechanism, just getting back into the lab and continuing to try was something this course really emphasized for me,” says Nell Horner ’24. “It’s something I will definitely take into future classes.”

“That lab is the first time students realize that all the skills that they’ve been learning from previous labs can be used here,” he says. It’s a nice bonus, he says, that this moment of synthesis is paired with a pleasant, fruity smell.

Beyond the course

Leggans is eager to bring as many students as possible into his research program, which focuses on synthesizing natural products, including antibiotics.

But even beyond that, Leggans hopes that anyone who takes organic chemistry — long known as an exceptionally challenging course — learns to take advantage of many different ways to master new skills and go further with their work through meaningful collaborative relationships. “I’m still talking to my science friends from Grinnell,” he says. “Community and collaboration are really important in the scientific world.”

SOC 295

SOC 295

The Sociology of Robots and AI

Taught by Professor of Sociology Karla Erickson

Course description

Students study tech ranging from robot pets to ChatGPT to understand how our relationships to machines have evolved and altered the social fabric.

Course materials

- Your Computer Is On Fire, essays

- Coded Bias (Netflix documentary)

- Automating Humanity, Joe Toscano

Key questions

Students relentlessly interrogate the impact of technology and artificial intelligence that has become ubiquitous, says Erickson. “We ask things like: What are we told about this technology? What skills do these products build up, and what skills do they diminish? What are some of the consequences of broad adoption of these new technologies?”

Essential project

As a final project, students choose a specific product or technology, from Apple Watches to the “like” button, then develop a short project to describe its importance. The projects are designed to be shared publicly as a podcast, video, or blog post.

The goal, says Erickson, is to show students they can meaningfully participate in this discussion. “I want students to contribute to the emerging social study of machine life,” she says.

“The reading we did on the addictive nature of technologies, and the profits to be made in engineering such addiction, has made me more conscious of how often and for what I use my devices,” says Owen Gould ’26.

Beyond the course

While Erickson says that the course often has immediate implications for computer science students, she also hopes the course informs students’ perspectives as they go on to pursue careers in other fields. “I want them to have a set of tools when they’re at the decision-making table, for example, if someone wants to automate hiring,” she says. “I want them to be able to think critically about when we automate things and for what purpose.”

Bio 150

Bio 150

Regeneration Biology

Taught by Professor of Biology Pascal Lafontant

Selected materials

- Principles of Regenerative Biology, Bruce M. Carlson

- Stem Cells: An Insider’s Guide, Paul Knoepfler

- Conversations with prominent scientists in the field

- Current primary research papers in regeneration biology and regenerative medicine

What it’s about

Humans can’t regenerate their limbs, spinal cords, or hearts — yet. But plenty of animals can: Axolotls can regenerate their brains, zebrafish can regenerate their spinal cords, and planarian flatworms can regenerate nearly every part of themselves, almost infinitely. In the course, students learn how the regeneration process works, practice methods used in regeneration lab work, and analyze the challenges and opportunities of applying it to humans.

Essential details

Students study the microscopic anatomy of biological tissue, practice staining techniques to highlight specific elements of these structures, and do assays to pinpoint exactly when cells are growing and dividing. Then, in small groups, students generate testable hypotheses and investigate cellular signaling pathways that drive the regeneration process using these techniques. The goal is not to replicate work that has already been done, but to pursue real research. “We’re trying to find something that nobody knows yet,” says Lafontant. “I want students to realize that they actually can do science.”

“This was the first class where I was able to take what I know, what I learned, and what I want to know, and combine it in a lab setting to gain knowledge that has not even been published yet,” says Evan Stoller ’26.

From classroom lab to research

Students often discover that the questions they want to pursue through research require more than a semester-long course. “In a way, that’s by design, because it helps me recruit students to my lab,” says Lafontant, whose own research focuses on zebrafish heart regeneration. Some student researchers go on to spend the summer in Boston, where they work with Lafontant’s collaborators at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Mellon Grant Fuels Gateways

Philosophy for Life and Introduction to Art History are two of several Grinnell courses that have benefited from a Mellon Grant that’s designed to help bring more students into the humanities.

The grant provides funding to develop or redesign introductory and 200-level courses to make them feel relevant and inclusive to today’s students. Other courses that have been reimagined include Humanities 101, Education 101, two introductory anthropology courses, and an Introduction to Shakespeare.

Shea, who helped redesign Grinnell’s Introduction to Art History course, says the grant has led faculty to align teaching approaches with the larger aims of a Grinnell education. For Shea, doing a deep dive on a smaller number of art objects through the new introductory class helps achieve that goal. “You’re not just ‘checking a box,’” she says of the smaller handful of objects they study. “You’re really understanding and engaging with them.”

Dobe says the newly developed Philosophy for Life course helps students immediately see the relevance of philosophy — and the humanities — to their lives. “Sometimes students have felt that philosophy is this erudite, inaccessible, obscure discipline — one they’re too intimidated to even enter,” she says. “This course is a way to bring philosophy down to earth and help students feel welcome in the department.”