American Journeys: The Quest

(photo above) Will Freeman took his Morgan three-wheeler on a 16,800-mile trek around the country, on a route planned entirely by students in the American Journeys class.

Photoshop illustration by Bruce Yang added Kesho Scott’s silhouette next to Freeman’s.

The clinking of coffee cups competed with the buzz of conversation at Saints Rest Coffee House, a favorite Grinnell setting for meetings of all kinds.

Most of the customers were unaware that something momentous was happening at the table where Kesho Scott DSS ’21 sat across from Will Freeman. Until that day, the two senior Grinnell faculty members had rarely spoken, although they had been faculty colleagues for decades on a small campus in a small town.

Scott and Freeman pose at the 1896 stadium in Athens, Greece, site of the first Modern Olympic Games.

Freeman and Scott were oblivious, focused only on each other and their conversation. Their coffee cooled, and the macaroons sat half eaten as the meeting stretched on.

What drew them together? What keeps them so close that they often finish each other’s sentences? What has kept them energized for seven years, as they have worked to co-develop and team teach a popular, innovative course they call American Journeys?

An Epiphany Over Coffee

It all started with a book, as many things do at Grinnell.

Freeman wrote the book in question, The Quest: On the Path to Knowledge and Wisdom. As a faculty member in physical education, Freeman taught sports psychology and sociology at Grinnell for many years. He also coached the men’s track and cross-country teams at Grinnell for four decades. The book tells the story of a transformative spiritual journey that Freeman took with his 12-year-old son in 2013.

When Scott read The Quest (a gift from her friend, Evelyn Freeman), the professor of American studies and sociology realized she had underestimated Will Freeman.

“It blew me away,” she says.

Their failure to connect sooner was the classic separation of academics and athletics, Freeman says, but also something more. “I was a little bit scared of her,” he says. “She’s this former Black Panther. She’s known for speaking her mind.”

Scott, however, was determined to know Freeman and to understand his ideas. She invited him to coffee.

“We need to talk,” she told him.

Inspiration Strikes

The meeting was life-changing for them both.

“I was blown away,” Freeman says. “Holy cow — talk about misrepresenting somebody and not understanding the depth of this person,” he says.

Before long, they were speaking freely — Freeman about his family, particularly his father, a former police chief. “I began to realize you can’t put all white boys in the same bucket,” Scott says. “They make choices that cost them, that use their privilege in a way that helps, and he was inspired by this.”

Scott began to understand why she was so drawn to Freeman — they have so much in common. For starters, they each had a parent who gave them permission to be different — in Scott’s case, her mother.

They decided to meet again the next day. They began to envision a class they would teach together, an interdisciplinary course that would bring together American studies, athletics, and more.

By the end of the second meeting, they had outlined the first version of their course, American Journeys.

Freeman (above) encouraged students to think of the classroom as a safe space.

Journey to Freedom

That first class in 2015 explored journeys that characterize American experience and identity. It offered students and professors alike an opportunity to understand the power of the American journey.

The most meaningful experience for many of the students was a midnight walk, following in the footsteps of enslaved people escaping to freedom. They walked more than five miles through the darkest hours of the night on the backroads of Poweshiek County.

Each student had researched a freedom seeker and took on that identity to re-enact the journey.

“To actually have them embody an enslaved person and know their story — that was quite incredible,” Scott says. “That person went from being buried and invisible to being visible and historical.”

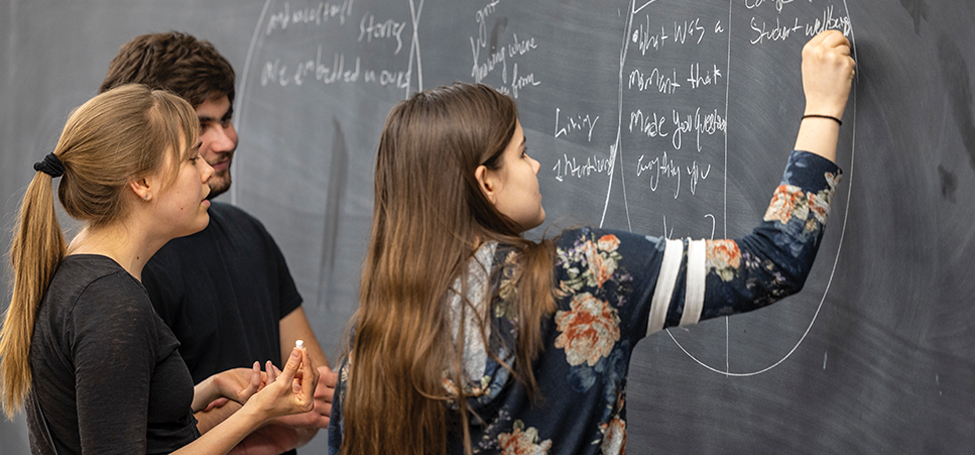

Scott says, “This is an active classroom where they’re their own actors. They get to look at their own lived experience. They do their own theorizing based on their experiences.”

Incredible, yes, but scary, too. “You hear dogs barking,” Freeman says. “Imagine knowing there also could be people out there at the end of a gun.” Behind the fear lurked a question: After you’re free — then what?

“That’s what we wanted them to see,” Scott says. “We are an open-ended culture that’s not finished.” Students had to grapple with the end of the journey — what will you do with freedom?

The Olympic Journey

(front to back) Lila Podgainy ’23, Julia Tlapa ’23, Bethany Willig ’23, and Kille at the ancient Olympic Games site in Olympia

The second course, taught in 2022, focused on social justice and the Olympic movement. For Freeman, a two-time U.S. Olympic Trials finalist in the pole vault, this subject was at the heart of his professional expertise.

Not so for Scott. “I just watched it on TV as a kid,” she says. With Freeman’s help, she learned about the back stories and internal struggles. She immediately saw how the Olympics reflected the major social upheavals of their times.

For instance, the politically charged Berlin Olympics of 1936 were intended to showcase Nazi white supremacist philosophies. Those hopes were largely dashed, thanks to athletes such as Jesse Owens, the Black American track star who earned four gold medals for the United States.

Freeman and Scott originally planned the class around course-embedded travel over spring break that would begin at Auschwitz in Poland, the most notorious of the Nazi death camps.

Then, in February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, and suddenly Poland was off limits. Scott and Freeman began the trip in Berlin instead, where students saw thousands of Ukrainian refugees. “People are being pushed all over, and the students could see it in real time,” Scott says.

Instead of Auschwitz, they went to Dachau, the Nazi camp near Munich, and then to the BMW plant next door, where Jewish prisoners were forced to work. The students saw the 1972 Olympics athletes’ village, and the apartment where the Palestine Liberation Organization took Israeli athletes hostage. The class also visited the first modern Olympics site in Athens; the ancient Olympics site at Olympia; the Nuremberg Trials site; and the Jewish ghetto at Munich.

One of the highlights happened in Grinnell, when Olympian Billy Mills joined the class by Zoom. Mills, a Native American track athlete, won Olympic gold in the 10K in 1964 — what Freeman calls the biggest upset in Olympic history. Mills spent more than an hour talking with the students and answering their questions.

“He just was remarkable,” Freeman says. Just as remarkable, former Grinnell President George Drake ’56 sat in on the class to hear Mills speak. Drake, who had been a track and cross-country standout as a Grinnell student, was in the latter stages of his battle with cancer.

Elisabeth Kille ’23 (right) and Emma Schaefer ’23 in Athens

“It meant the world to me and Will because it was an affirmation that we are doing something right,” Scott says.

“He was a graduate of Grinnell, not just president. He loved this school like hell.”

The Journey Within

In spring 2023, American Journeys turned inward, focusing on the quest to discover and understand the true self.

“We are so often defined from the outside, through social media and social comparison,” Freeman says. Over time, the comparisons build up. “Layer after layer covers up the authentic you.”

The third iteration of the course took students on an inward journey to rediscover their true selves. “We began to realize that this question of going inward isn’t new,” Scott says. “We’re just updating the idea for this moment.”

The subtle message, Freeman says, is that you need to change or hide your true self to fit in.

He wanted the students to understand that process and how we can intervene. He and Scott challenged the class to rediscover their authentic selves, buried by years of comparisons and conformity.

An Empowering Environment

Looking inward created a unique classroom experience, says religious studies major Maya Sciaretta ’25.

Each class began with guided meditation — a routine that Sciaretta says became a welcome break from daily stress. “I loved having the opportunity to clear my head and to work through the thoughts and emotions I carried into the classroom,” she explains.

The professors created an empowered, critical, and reflective environment, says Agatha Fusco ’25, an economics and Spanish major. “Their teaching felt fueled by creativity and passion in a way that filled their classroom with an energy that I think can sometimes be hard to find.”

Students responded by opening up as never before. “We were encouraged to share personal stories and to share our reflections on a consistent basis. Dr. Scott and Coach Freeman were also ready and willing to share their own stories and taught us about their journeys as we explored our own.”

Hannah Biles ’24, a sociology and Spanish major, adds, “I stepped away from every class feeling more grounded in who I am, more grateful for the people in my life, and more confident in our ability to heal ourselves while we support others in their personal healing journeys.”

Hugh Werner ’25, a biological chemistry major, says the class helped him cope with a difficult period in his life.

“I hit rock bottom last semester — socially, physically, emotionally,” he says. “I had to face the real world earlier than I thought.” Even though he got support from his friends and teammates on the football team, he was struggling.

“This class kept me on my feet.”

Inward Expeditions

Near the end of the semester, several guest speakers visited the class. In the spirit of looking inward, President Anne Harris shared an important part of her personal journey with the class — her arrival in the United States at age 9 from Switzerland, where she had lived with her Swiss mother and American father. She arrived with only a few words of English and had to begin learning the language from scratch.

Fusco says she appreciates how honest and forthcoming Harris was. “I think, out of a respect and understanding for what my fellow students and I were doing in that class, President Harris did an excellent job of looking inward and providing genuine reflections.”

Fusco says she appreciates how honest and forthcoming Harris was. “I think, out of a respect and understanding for what my fellow students and I were doing in that class, President Harris did an excellent job of looking inward and providing genuine reflections.”

Harris says her experiences were not so different from the questions and anticipation that many first-year students face. “Students who come to Grinnell have made the decision to journey off the beaten path,” Harris says. “That brings with it a whole set of questions of purpose and belonging that fellow students from all over the world are also asking themselves.”

Harris says she appreciates the unique nature of the American Journeys course. “I loved it,” she says. “This is how a liberal arts education asks hard and necessary questions.”

An Ongoing Pilgrimage

Freeman and Scott, who are already planning the next American Journeys class, agree that the course has energized them as never before. “It has revitalized my teaching,” Scott says. “We are able to really think and teach courses that are from our hearts.”

Freeman agrees. “I’ve found another avenue to try to make a difference. And that is the most powerful thing in the world.”

Emma Schaefer ’23 (right) with Elle Albrecht ’24 and Nina Baker ’24 at the Berlin Wall

Grinnellians Go Places through the Global Learning Program

Grinnell’s commitment to creating global citizens who can navigate the world’s complexities has never been more important.

Thanks to a generous $4 million gift from Susan Holden McCurry ’71 and her family foundation, the Roland and Ruby Holden Foundation, Grinnell students are experiencing the world firsthand through course-embedded travel and other global academic initiatives. It’s all part of Grinnell’s Global Learning Program, stewarded by the Institute for Global Engagement.

GLP allows Grinnellians to travel as a core part of their academic experience. Courses that include embedded travel are centered on first-year classes that focus on global issues; occasionally, they may include upper-level classes, such as the 2022 American Journeys trip to Greece, Poland, and Germany.

GLP participants learn about their own place in the world and how to adapt and problem-solve as they explore new cultures and places in a course designed by two faculty members. Through their engagement in global learning, they not only enhance their Grinnell education, they also acquire the skills they need to thrive in a fast-changing world. They learn about diverse perspectives and about their own personal and social responsibilities as citizens of the world.

Students participating in the GLP class pay a program fee based on their financial need. Thanks to the support of donors like Susan Holden McCurry, generous scholarships are available to help make such formative global experiences more financially accessible to all students, underscoring Grinnell’s institutional commitment to equity and inclusion.