Learning French in Prison: À Quoi Bon?

Roughly translated, this phrase means, “what’s the point?” This is what Cliff said to me on the first day of French class in the Newton Correctional Facility. To be more precise, he said, “I don’t want to take this class. I’m not gonna learn anything.” His lack of enthusiasm was echoed by a couple of the 15 men enrolled in French 101 via the Liberal Arts in Prison Program. Most of them, though, were excited by this opportunity.

The Liberal Arts in Prison Program offers incarcerated students a full-fledged college program equivalent to the first year at Grinnell. Unlike students on campus, incarcerated students do not get to choose their courses, and thus Cliff was obliged to take what was on offer in fall 2018 — French 101.

Undaunted by Cliff’s rejection, I introduced myself, as I do in any first class, with an overly theatrical “Bonjour!” and a handshake with each student.

“Je m’appelle Claire,” I slowly and clearly declared to each student, pointing to myself, eyebrows arched, voice rising as if engaging with a newborn. “Comment t’appelles-tu?”

Stunned silence. Dinner-plate-sized eyes stared back at me in unspoken terror — you’re not actually gonna make us speak French, the eyes said. Not on the first day at least!

“Gemma Pell Carl.”

We made it around the room. The ice was broken. Ça va? My voice went up. Ça va. My voice went down. They dutifully repeated after me, rising intonation, falling intonation. And just like that, they were having their first French conversation, introducing themselves and asking and answering “How goes it?” “It’s going.” We added on “bien, mal, and comme-ci, comme-ça” and soon they were all doing a Gallic pout and shrug. “Ça va comme-ci comme-ça.”

By the end of the first lesson, Cliff was still dubious but he continued to show up along with the others for the next 13 weeks, learning to conjugate verbs — first the irregulars “to be” and “to have,” and then the regulars — to love, to travel, to study; memorizing vocabulary about the classroom, about family and friends, about sports and free time activities; engaging in ever more complex conversations — describing people, ordering food, organizing a trip to Tahiti.

À quoi bon?

It was not lost on me, nor on the French majors who accompanied me to tutor in the prison, that many of the topics we covered in French 101 are far removed from these students’ daily lives. What’s the point of learning to kiss hello the French way or order a coffee in a typical French café, or plan that trip to Tahiti? What’s the point of learning conjugations and vocabulary that slips away as fast as it is learned?

The class was hard. As hard as it is for first-year students on campus. It moved quickly, so as soon as they learned one grammatical point, they were racing to the next. And the men don’t have access to technology like our on-campus students do. They didn’t have cute little instructional videos or self-correcting workbooks to guide them on their homework. They had to learn a lot of the material on their own and with the help of tutors, so that they were prepared to speak in class. During class, we played games to make it fun — Pictionary for vocabulary, relay races for verb conjugations, fun role-plays.

But still, à quoi bon? Cliff complained.

I told the men about learning strategies to make learning stick, namely spaced repetition and retrieval (aka self-quizzing in 20-minute chunks a few times a day). “You don’t have to work harder or spend more time,” I told them, as I do my on-campus students. “You just need to exercise your brain like you do your muscles — with sets of repetitions. And this is advice you can use in any other learning situation,” I said. “It’s not just for learning French!”

And there’s my first answer to the “à quoi bon” question: learning French is an exercise in intellectual discipline, a way to create learning habits, to set and achieve goals. It is also, of course, a way to open the doors of the prison, to get a glimpse of another world and other ways of being, to learn about different education systems, about café culture, about football/soccer, and even fashion, to make cultural and linguistic comparisons and connections across Francophone cultures.

And this is fundamentally what a liberal arts education seeks to do, as the College’s mission statement tells us: “Knowledge is a good to be pursued both for its own sake and for the intellectual, moral, and physical well-being of individuals and of society at large.”

My incarcerated students, my tutors, and I were all patently aware that they may never have the chance to speak French in a real Francophone context. But they are also equally aware that the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake and the expansion of their horizons is in and of itself good.

When I asked Cliff if he’d learned anything, he thought for a minute and replied, “I learned that France has a really strong soccer program because of the waves of immigration after the war. I learned that I have to say cwah-sant, not crescent, in a café. I learned that knowing a language gives you a much deeper appreciation of the culture than, like, when I was in Iraq in the Army and only knew a few words. Most of all, I learned that I could learn a foreign language.”

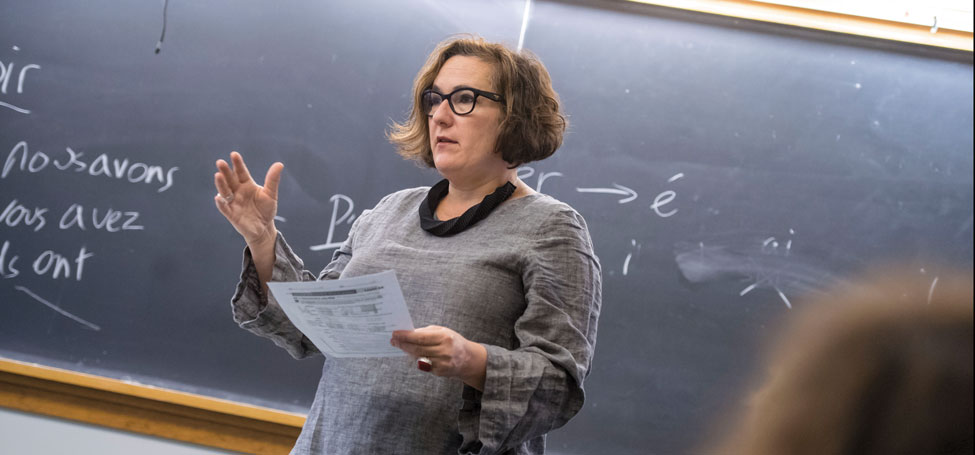

Claire Frances taught for 21 years at Grinnell, including eight in the Department of French and Arabic. She also directed the Alternate Language Study Option (ALSO) program and in 2017 created the Language Learning Center.

Claire Frances taught for 21 years at Grinnell, including eight in the Department of French and Arabic. She also directed the Alternate Language Study Option (ALSO) program and in 2017 created the Language Learning Center.