Planting Seeds of Hope

Anyone walking by the Grinnell home of Harold Kasimow on a Friday night in the 1970s might have paused to take in the sounds and sights coming from the modest two-story house. They might have wondered about the candlelight flickering in the windows and the sounds of singing, clapping, and laughter drifting through the evening air. They might have glimpsed the shadows of dancers spinning around the room.

For Jewish students at Grinnell College in those days, Kasimow’s home was a magnet on Friday nights. With no temple or rabbi in the community, Kasimow served as the Jewish student adviser. He and his wife welcomed students to their home for Shabbat, the Jewish day of rest and celebration that begins Friday at sunset and ends when three stars appear in the sky at nightfall on Saturday.

With no budget, one of the students baked the challah and Kasimow bought the wine. “We rarely studied,” says Kasimow. “We mostly sang songs and danced — we said the prayers.”

He adds, “I really loved Friday nights.”

A Way of Being

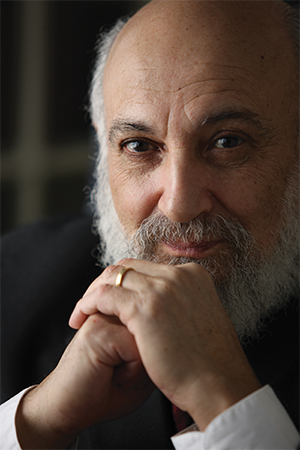

The love Kasimow feels for his former students is returned in full, even decades after graduation. Since 1972, he has been a faculty member in religious studies. Now emeritus, Kasimow was the first to be named the George Drake Professor of Religious Studies. He is a beloved teacher and adviser at the College with an international reputation as a writer and speaker on interfaith dialogue.

The love Kasimow feels for his former students is returned in full, even decades after graduation. Since 1972, he has been a faculty member in religious studies. Now emeritus, Kasimow was the first to be named the George Drake Professor of Religious Studies. He is a beloved teacher and adviser at the College with an international reputation as a writer and speaker on interfaith dialogue.

Among his many students, colleagues, and friends around the world, Kasimow is known for his empathy, his understanding, his thoughtful silences, and his kindness.

Robert Gehorsam ’76 arrived on campus the same year Kasimow joined the faculty. A religious studies major, Gehorsam made sure to take at least one of Kasimow’s courses every semester.

As an alum, Gehorsam’s volunteer work as Alumni Council past president and more has often brought him to campus. On one such visit, he happened to run into his former professor. They walked across campus together, chatting as they went.

Their conversation flowed naturally, as if they had been apart for two weeks instead of two decades. The occasional silence felt comfortable. “That’s the thing I still just adore about him,” Gehorsam says. “There was always a quiet space that he provided to let you think and reflect. He always has humility and humbleness. Who doesn’t love that?

“As a way of being, he’s still an inspiration to me,” Gehorsam says.

To honor their professor, Gehorsam and Grinnell Trustee Jeetander Dulani ’98 have created the Harold Kasimow Internship for Interfaith Dialogue Endowed Fund. The fund supports students who want to learn and work with organizations and groups that use interfaith dialogue to pursue social reconciliation and healing.

“We realized Harold had made such a difference, not just in our lives, but in so many others’, and his view of interreligious dialogue, pluralism, and engagement is a really powerful one,” Dulani says.

Henry Rietz ’89, who is now the George Drake Professor of Religious Studies and chair of the Department of Religious Studies, says the internship fund is a beautiful way to honor a man who has given so much to his students and the world. “Professor Kasimow has dedicated his life to interreligious dialogue and he is still publishing books, writing op-eds, and active in making the world a better place,” Rietz says.

The Grave

If the world had been a better place when Kasimow was a child, he might have been a fisherman, like his father.

He might have stayed in the small village north of Vilnius, Lithuania (then part of Poland), where he was born. He would likely have learned the trade from his father, Norman, a successful and prosperous fisherman.

The Nazis changed everything.

Kasimow was just 4 years old in 1942 when Norman Kasimow took his family into hiding in a shallow pit under a farmer’s cattle barn. For 19 months and five days, they never saw the sun. They barely spoke or moved. At night, Kasimow’s father slipped out to find enough food to keep them alive.

They called their hiding place the grub, or hole. Sometimes, they called it the keyver — the Yiddish word for grave.

“We were already buried there,” Kasimow says.

“It was all strange to me when I got out. I’d never seen the light. I’d never been out of the hole. It was always pitch black.”

Kasimow (second from left) with the older brother of a friend (left) and other refugees on their way to Germany after leaving Poland in 1946.

The Promised Land

The family survived, thanks to the determination of Kasimow’s father. But a year and a half of near starvation, constant fear, and almost no movement had taken its toll. “We were like skeletons,” Kasimow says.

When the Russians liberated the region in 1944, Kasimow and his family found that the world was still a dangerous place, for civilians as well as soldiers. Kasimow’s parents decided to leave the area that had been their home and travel to the American-controlled zone in Germany.

The trip was long and hazardous. Once the family reached Germany, they spent about three years in Bad Reichenhall, a large displaced persons camp. It took time for them to find someplace to go. Laws in the United States limited the number of immigrants who could be allowed in. “We had my father’s sister to guarantee that if we came, she would support us,” Kasimow says. In 1949, they found their way to the United States and settled in the Bronx.

Kasimow with his sisters, Rita and Miriam, at the Bad Reichenhall Displaced Persons Camp in 1947 or 1948.

It was a chance for a new life — a life of opportunity and education, of making friends and playing handball in the street, of basking in the sunshine and having enough to eat.

A sort of survivor’s mentality clicked in for Kasimow. Like many others, he turned his back on the Holocaust and focused on the future. His parents didn’t speak of it, and neither did he.

It would be many years before Kasimow began to re-examine the trauma of his early life.

Transformation

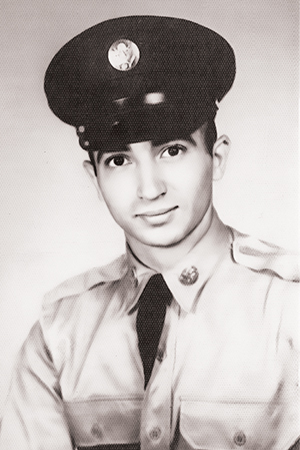

Kasimow went to Yeshiva University High School and then to the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, studying Hebrew literature and Jewish tradition. Later, after serving in the U.S. Armed Forces, he earned a master’s and doctoral degrees in religion at Temple University.

Through his studies, Kasimow met two influential teachers: Bernard Phillips (“an incredible, fascinating human being” who influenced Kasimow’s teaching style); and his mentor and role model Abraham Joshua Heschel, a Holocaust survivor, Polish-American rabbi, and one of the leading Jewish theologians and philosophers of the 20th century.

Kasimow was drafted into the U.S. Army (“an invitation from Kennedy that I couldn’t refuse”) in 1961. He served in Okinawa and Thailand.

“I devoted my academic career to writing about Heschel, which changed my life,” Kasimow says.

They introduced Kasimow to ideas that would shape his thinking and his career. Phillips launched Kasimow’s lifelong interest in Asian religions, particularly Hinduism and Buddhism.

When Kasimow read Heschel’s article “No Religion Is an Island,” he was struck by the statement that “diversity of religions is the will of God.”

Kasimow learned that what matters most is not the faith a person belongs to, but the person’s humanity. He embraced Heschel’s understanding of the true aim of religion — “to transform us, to have concern for others.” This concern is what makes us truly human, Kasimow says.

The Yiddish word for “human being” (mensch) describes someone who is dignified and compassionate, demonstrating integrity and a never-ending search for truth. To be a mensch is one of the greatest callings we can aspire to.

So began Kasimow’s dedication to interfaith dialogue. Every human being is created in the image of God, Kasimow explains. This principle is the foundation of interfaith dialogue. To downgrade a human being is to downgrade God.

“The hope of interfaith dialogue is to listen to each other so we can begin to see, to try to understand another person,” Kasimow says. “Transformation is always a possibility.”

Throughout most of his decades-long faculty career at Grinnell, Kasimow kept his Holocaust memories locked away. He wasn’t a Holocaust scholar. Because he had been a child during the Shoah (the Hebrew word for catastrophe, often used to refer to the Holocaust), he believed others were better qualified to write and speak on the subject.

It was only much later that Kasimow began to see how the Holocaust and interfaith dialogue were connected. If the principles of interfaith dialogue had been upheld — that every human being is created in the image of God — the Holocaust would have been impossible, a contradiction of God’s will.

“It has occurred to me in recent years that I became so involved in dialogue because of my early life that I’d never wanted to think about,” he says.

A Life Dedicated to Interfaith Dialogue

Kasimow (left) with President George Drake ’56 in 1989 when Kasimow was named the first George Drake Professor of Religious Studies.

Kasimow is retired now, but his work on interfaith dialogue as a way to foster the common good continues at a remarkable pace. His list of books, lectures, and publications is impressive.

His most recent books, Love or Perish: A Holocaust Survivor’s Vision for Interfaith Peace (2021, iPub Global Connection) and Interfaith Activism: Abraham Joshua Heschel and Religious Diversity (2015, Wipf & Stock) have earned glowing reviews. Kasimow is currently working on major revisions to his book Divine-Human Encounter: A Study of Abraham Joshua Heschel.

An internationally renowned Jewish scholar, he has traveled the world to speak about interfaith dialogue, collaborating with scholars, leaders, and theologians of many faiths — including meetings with Pope John Paul II and Pope Francis.

More and more, Kasimow is embracing his role as a Holocaust survivor. “There are not so many Holocaust survivors who can still tell their story, which seems to be becoming more important every day,” he says.

Kasimow frequently speaks to groups about the Shoah. He values speaking at schools most of all. “Young people ask really good questions,” Kasimow says.

After speaking at a school in Minnesota, a mother shared her gratitude for Kasimow’s interactions with her son, who suffers from depression. “Talking with you helped him to see hope in the idea that things will get better, and we can survive these difficult times,” she wrote. “Please know that by sharing your story and by carrying light from the (literal) darkness, you are planting a seed of hope for future generations.”

“I was very moved by that,” Kasimow says.

This engagement with young people encourages Kasimow to continue speaking and writing about his Holocaust experiences, although it is never easy for him.

“I don’t want to see any more children lose their childhood,” he adds.

He still doesn’t feel that he is a Holocaust scholar. “I’m a Holocaust survivor,” he says.

Kasimow is frequently asked if he is optimistic. “I am hopeful for the future,” he says, “because there really is no other option for humanity.”

Kasimow (center) and his friend and colleague Alan Race met Pope Francis at the Vatican in 2018 and presented him with a plaque highlighting their book, Pope Francis and Interreligious Dialogue.